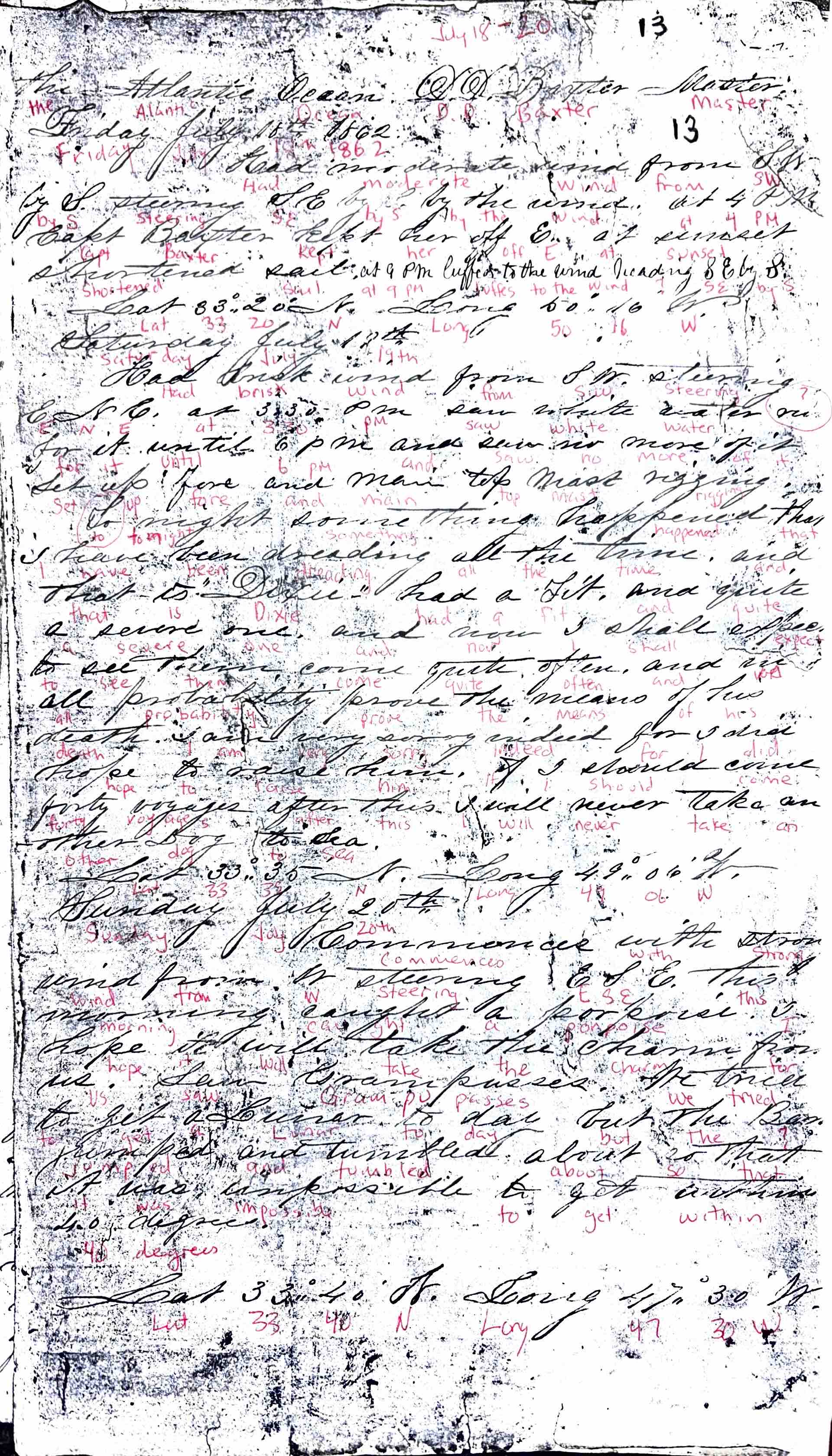

July 18 - 20, 1862

Pg. 13 of 39

the Atlantic Ocean D. D. Baxter Master

Friday July 18th 1862

Had moderate winds from SW b S. Steering SE by S by the wind at 4pm. Capt Baxter kept her off E at sunset. Shortened sail at 9 pm luffed to the wind heading SE by S.

Lat. 33 20 N Long 50 16 W

Saturday July 19th

Had brisk wind from S.W. steering E. NE at 3:30 pm. Saw white water ? for it until 6 pm and saw no more of it. Set up fore and main top mast rigging. Tonight something happened that I have been dreading all the time. And that is Dixie1 had a Fit and quite a severe one and now I shall expect to see them come quite often and in all probability prove the means of his death. I am very sorry indeed for I did hope to raise him. If I should come forty voyages after this I will never take an other dog to Sea.

Lat. 33 35 N Long 49 06 W

Sunday July 20th

Commences with strong wind from W steering E.SE this morning caught a porpoise. I hope it will take the charm for us. Saw Grampusses. We tried to get a Lunar2 to day but the Bark jumped and tumbled about so that it was impossible to get within 4.0 degrees.

Lat 33 40 N Long 47 30 W

1 Dogs on ships were not common among general crew, but they did appear as: Captain’s or officer’s pets, Ship mascots, Expedition dogs (Arctic especially). They appear in paintings, engravings, and photographs, confirming real historical practice. The Solon’s dog “Dixie” fits well into the tradition of officer-kept companion animals.

2 Bob Fitch: Lunar Distances To calculate your longitude, you need to know the current time in Greenwich, England, where the 0-degree meridian is. So the “ship’s clock” always shows Greenwich Time. A simple example: If, on your ship, you see the sun directly to the south, it is noon on your ship. If the ship’s clock at that moment is showing 3 pm, then you know that, 3 hours ago, it was noon in Greenwich. Since the earth rotates to the East 15 degrees every hour, your longitude is 45 degrees West. At the time of this journal, clocks were good enough for a normal ocean crossing. So that after, say, 2 weeks, the error might be 30 seconds, resulting in a navigational error of about 7 miles, good enough to make land at the intended destination. But a whaling ship was months at sea without seeing land, so they needed a way to set the clock now and then. This is where “lunar distances” come into play. With a sexant, you measure the angular distance between the moon and a known star. You also measure the height of the moon and of the star above the horizon. With this information, and with the Nautical Almanac and a lot of calculations, you get Greenwich Time and can set the ship’s clock. BUT: those measurements, especially the moon-star distance, are very hard to take accurately if the ship is unsteady due to wind and waves. So the navigator would take advantage of any time the ship was becalmed to try to get a good “shot”. And this is why Duntlin is disappointed that, because of the ship’s motion, his reading is only accurate to about 4.0 degrees. Whereas a good reading would be accurate to about 0.1 degrees.