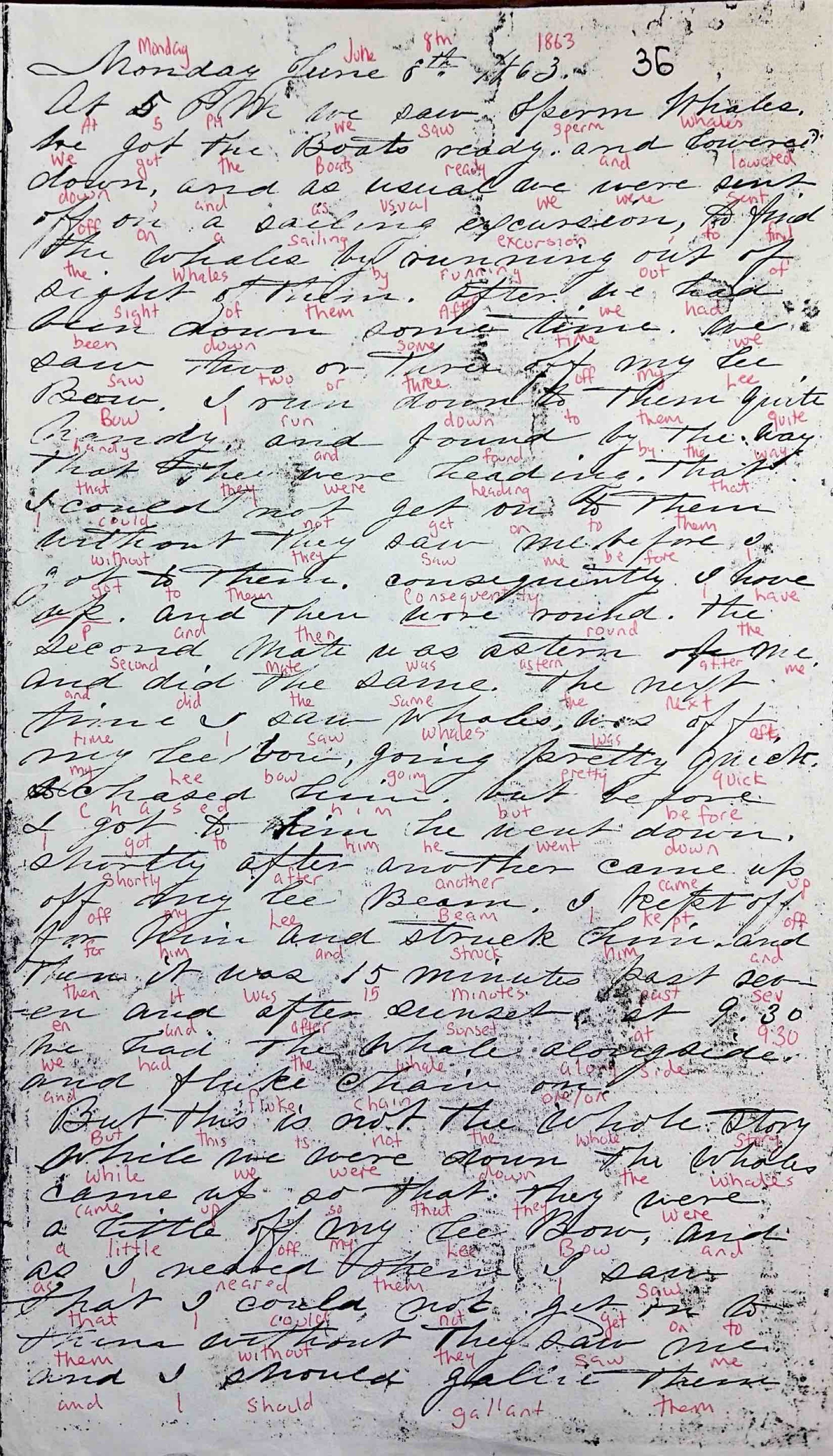

Monday June 8th 1863

Pages 36 - 37 of 39

Page 36

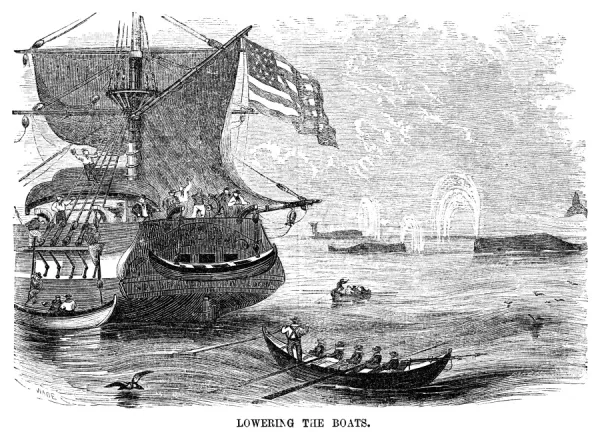

At 5 pm we saw Sperm Whales. We got the Boats ready and lowered down, and as usual we were sent off on a sailing excursion to find the whales by running out of sight of them. After we had been down some time we saw two or three off my Lee Bow1. I run down to them quite handy and found by the way that they were heading that I could not get on to them without they saw me before I got to them. Consequently I sheered off and then came round2. The second mate was astern after me and did the same.

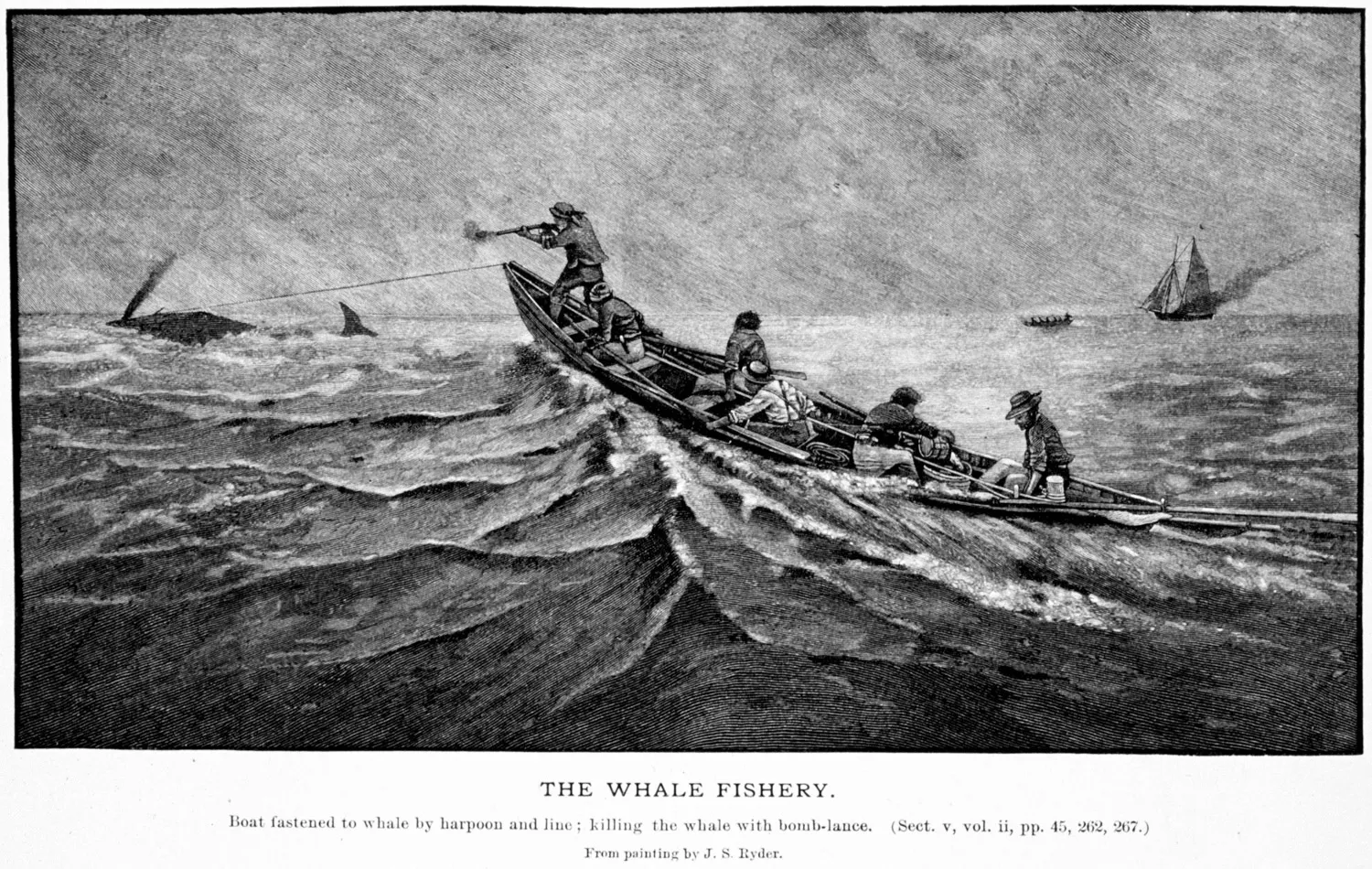

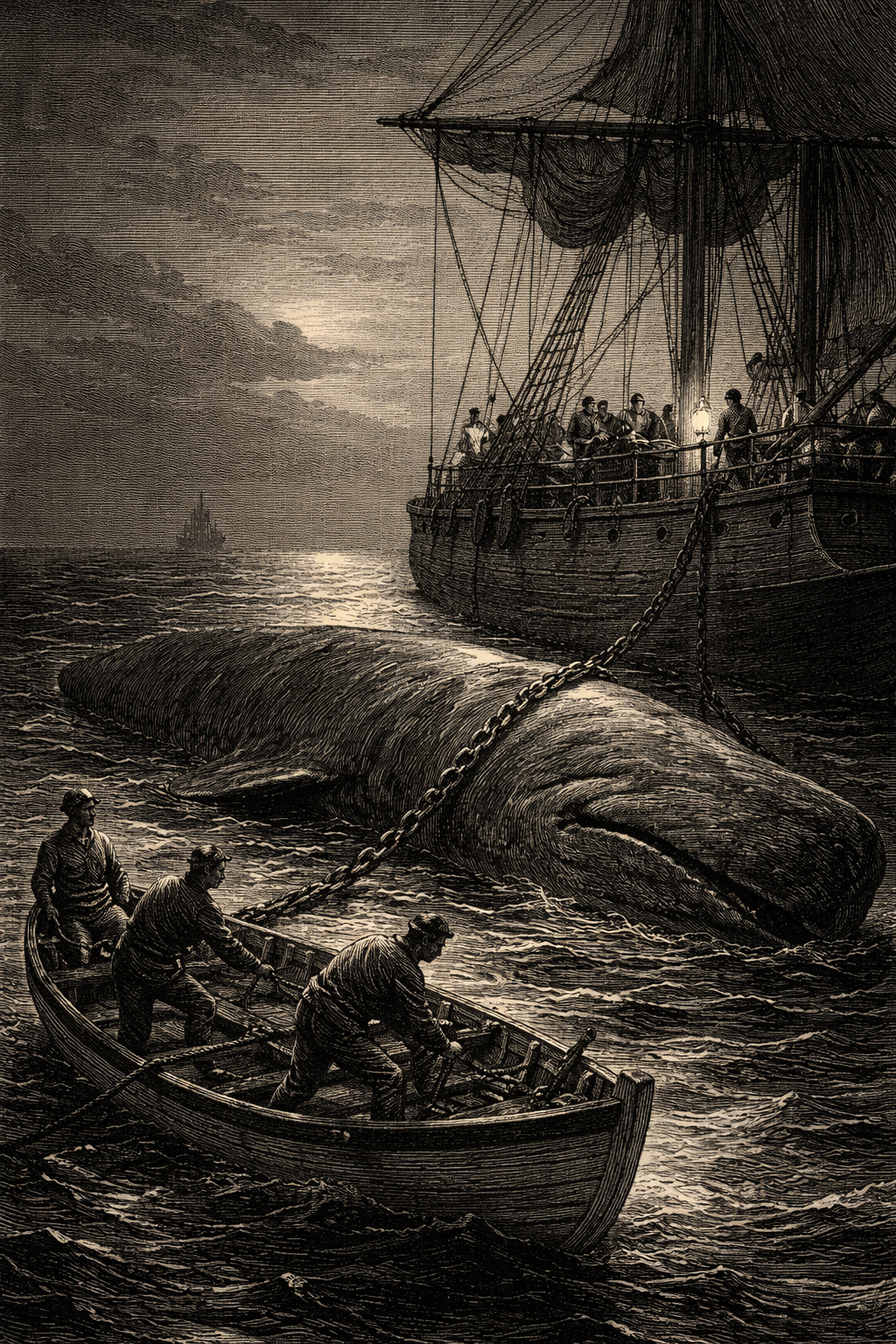

The next time I saw whales was aft my Lee Bow, going pretty quick. I chased him but before I got to him he went down. Shortly after another came up off my Lee Beam. I kept off for him and struck him and then it was 15 minutes past seven. And after sunset at 9:30 we had the whale alongside and fluke chain on.

But this is not the whole story while we were down the whales came up so that they were a little off my Lee Bow. And as I neared them I saw that I could not get on to them without they saw me. And I should gallant them3.

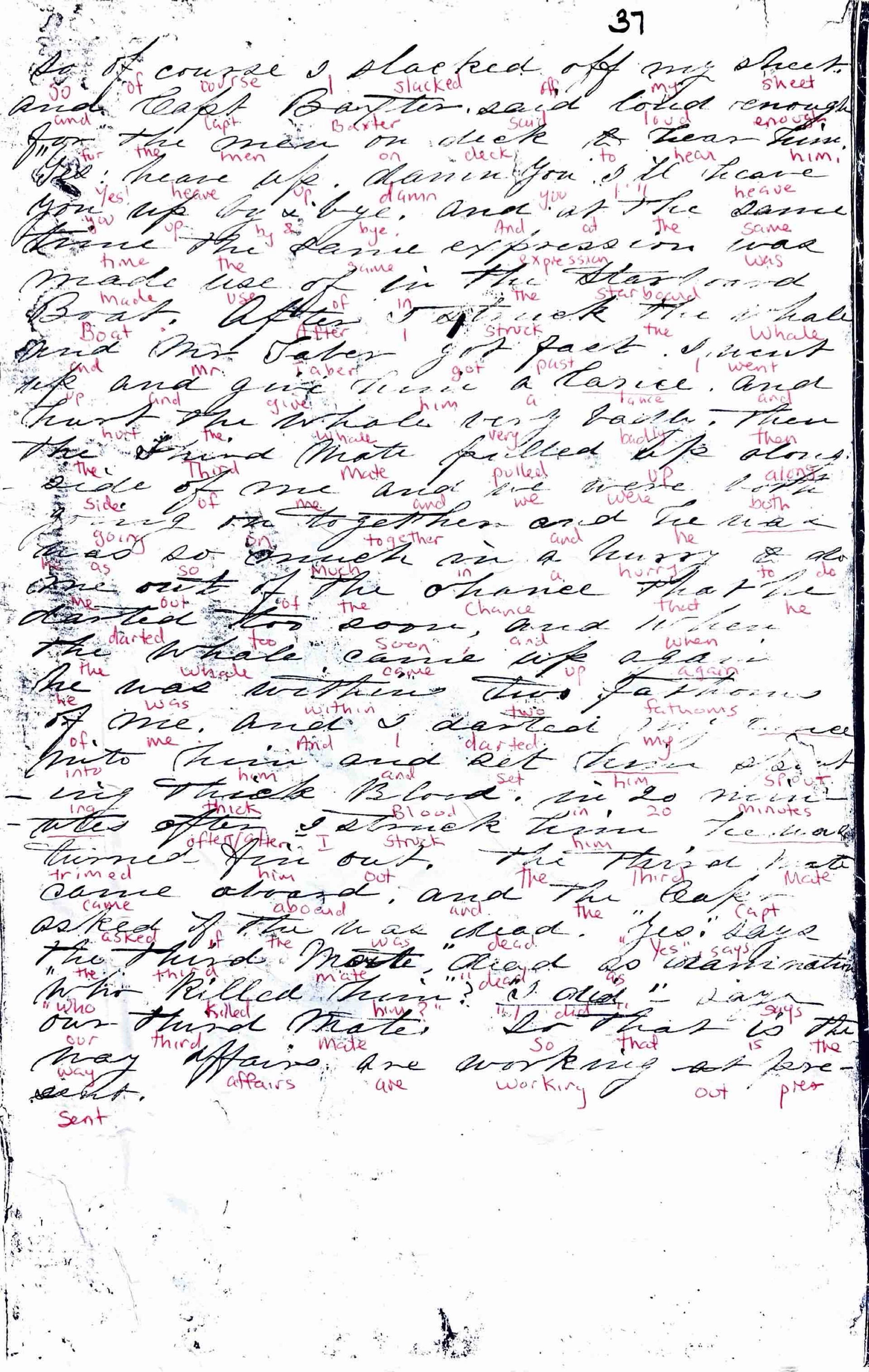

Page 37

So of course I slacked off my sheet4.

And Capt Baxter said loud enough for the men on deck to hear him, “Yes heave up, damn you. I’ll have you up by and bye.”5

And at the same time the same expression was made use of in the starboard Boat.

After I struck the whale and Mr. Taber got past I went up and give him a lance. And hurt the whale very badly then the Third Mate pulled up along side of me and we were both going on together and he was so much in a hurry to do me out of the chance that he darted too soon6 and when the whale came up again he was within two fathoms of me7. And I darted my lance into him and set hm spouting thick Blood8. In 20 minutes after I struck him he had turned fin out9.

The Third Mate came aboard and the Capt asked if the was dead.

“Yes,” says the Third Mate. “Dead as herring”

“Who killed him?”

“I did” says our Third Mate10.

So that is the way affairs are working out present11.

1 “Lee” refers to the downwind side of a vessel. The “lee bow” and “lee beam” describe relative positions off the whaleboat, indicating both wind direction and tactical approach. Approaching from the lee was essential for stealth, as whales could detect disturbances carried downwind.

2 To “sheer off” was to turn a whaleboat away sharply to avoid alarming whales whose heading made a close approach impossible. “Came round” indicates resuming a new approach after altering course. These maneuvers reflect experienced whale sense rather than hesitation.

3 In whaling usage, to “gall” or “gallant” whales meant to disturb or alarm them, causing them to sound prematurely. The term does not imply gallantry but rather an error in approach that spoiled the chance of a strike.

4 Easing the sheet reduced sail pressure and speed, allowing the boat to approach quietly. Slacking the sheet at the wrong moment could draw criticism from officers eager for aggressive pursuit.

5 Orders shouted loudly from the ship to whaleboats were often performative as well as directive. Making such remarks “loud enough for the men on deck to hear” suggests an intention to publicly undermine authority or competence.

6 In whaling practice, credit for killing a whale often depended on whose weapon ultimately proved fatal. A premature dart could still position an officer to claim the kill if the whale later died, even if another man delivered the decisive wound.

7 Two fathoms (approximately twelve feet) indicates extremely close proximity between boats, underscoring both the danger of the situation and the intensity of competition for credit.

8 Heavy bleeding from the blowhole signaled that the whale had been mortally wounded. In whaling accounts, this was widely understood as evidence of an effective and likely fatal lance.

9 To “trim out” a whale meant that it had died and settled in a stable position, often with fins or flukes exposed. This marked the end of the chase and the beginning of securing the carcass.

10 Disputes over who killed a whale were not uncommon aboard whalers, particularly when lay (profit share), reputation, or authority were at stake. Such conflicts often reflected deeper tensions within a ship’s hierarchy.

11 This understated conclusion is characteristic of maritime grievance narratives, in which repeated incidents accumulate into a broader critique of leadership rather than a single complaint.