Wednesday May 27th 1863

Pg 34 of 39

Wednesday May 27th 18631

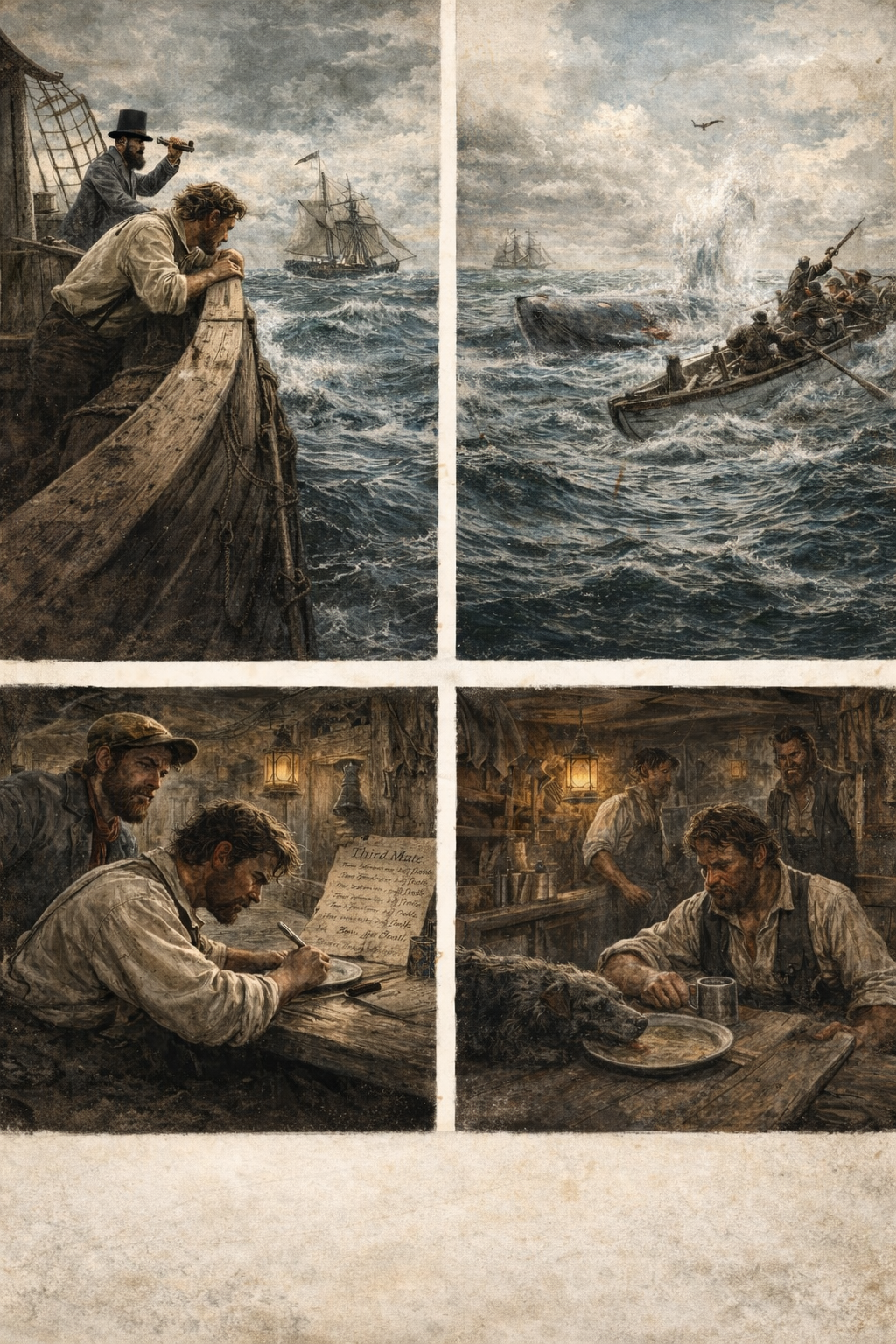

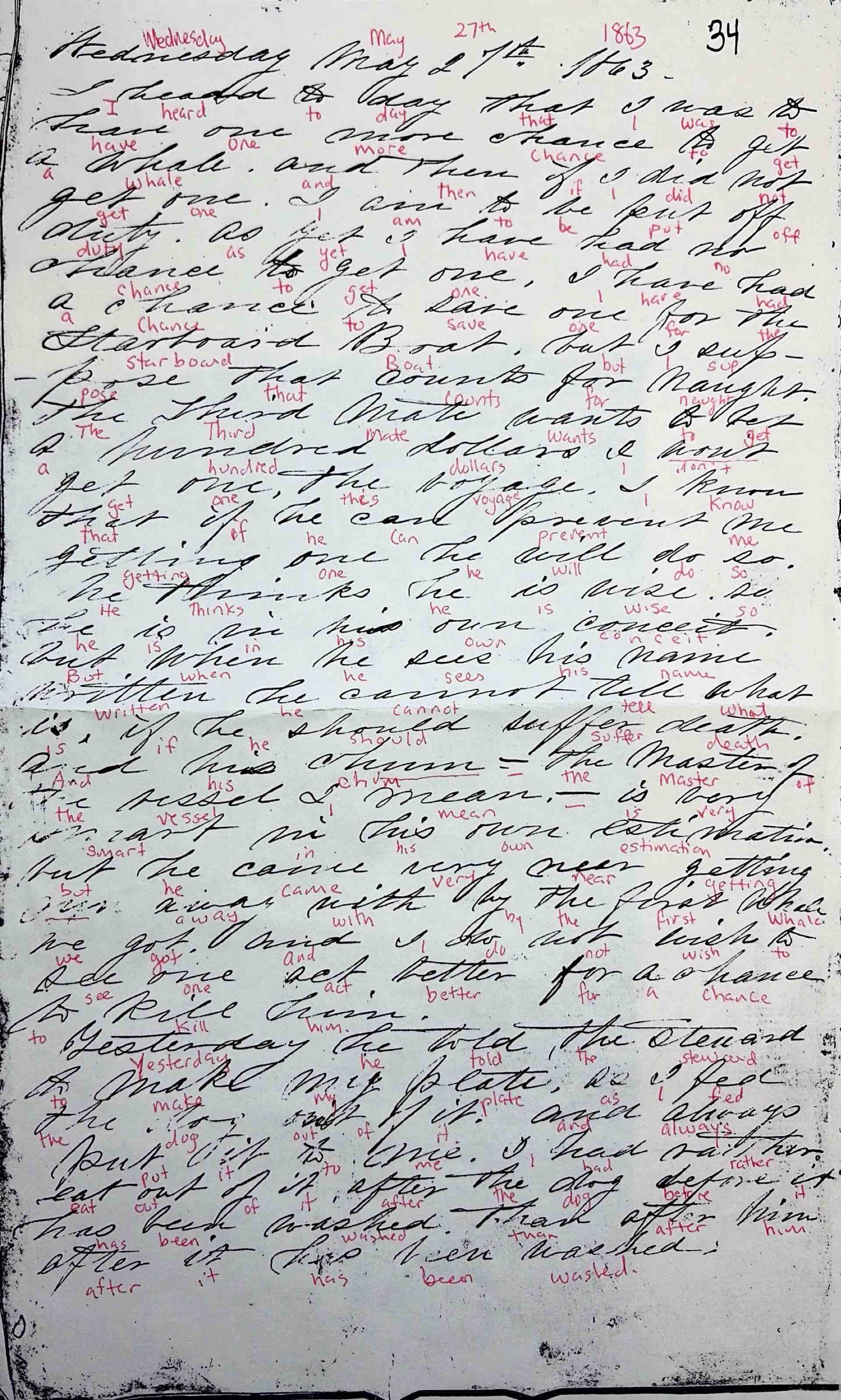

I heard to day2 that I was to have one more chance to get a whale. And then if I did not get one I am to be put off duty3. As yet I have had no chance to get one. I have had a chance to save one (whale) for the Starboard Boat but I sup-pose that counts for naught.

The Third Mate wants to get a hundred dollars [if] I don’t get one this voyage. I know that if he can prevent me getting one, he will do so. He thinks he is wise, so he is in his own conceit. But when he sees his name written he cannot tell what is if he should suffer death4. And his chum - the Master of the vessel, I mean - is very smart in his own estimation. But he came very near getting push away with by the first Whale we got5. And I do not wish to see one act better for a chance to kill him.

Yesterday he6 told the Steward to make my plate, as I fed the dog out of it, and always put it to me. I had rather eat out of it after the dog before it has been washed than after him after it has been washed7.

1 On May 27, 1863, the major event in the U.S. was the first major Union assault during the Siege of Port Hudson in Louisiana, a critical Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. This battle marked the first major engagement where African American regiments — the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards — were used in a significant combat role. They made multiple heroic but unsuccessful charges, proving their valor to a skeptical public. Elsewhere, CSS Chattahoochee Explosion: In Florida, the Confederate gunboat CSS Chattahoochee suffered a catastrophic steam boiler explosion on the Apalachicola River, resulting in the deaths of 19 crew members. Elsewhere, During the Siege of Vicksburg in Mississippi, the ironclad gunboat USS Cincinnati was sunk by Confederate river batteries while attempting to neutralize them.

2 Who told him? Some un-named sailor or sailors are passing information to Duntlin.

3 Does this mean that John T Duntlin has not been credited with getting a whale on this journey that began in June 1862? Within the nineteenth-century whaling lay system, it was customary for a single individual to receive credit for “getting” a whale, even though the chase and killing were the result of coordinated labor by an entire boat’s crew. As a result, officers who controlled opportunities to strike could effectively determine who advanced professionally and who did not. This system, described by Alexander Starbuck and reflected in contemporary narratives such as Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, helps explain complaints by men who, like Duntlin, participated in successful encounters yet were denied formal credit.

4 Duntlin, whose literacy acumen is evident, is pointing out that the Third Mate could not read his own name to save his own life. In mid-19th-century whaling, officers were expected to read logbooks, accounts, and correspondence. Illiteracy at that level suggested not just ignorance, but unfitness for command. Duntlin is implicitly asking how a man can judge others, control men, or profit from a voyage when he cannot even read his own name.

5 Duntlin notes that the Captain himself narrowly escaped being killed by the first whale taken on the voyage, yet he insists that he would not wish for a whale to perform better merely to kill him—an assertion that underscores Duntlin’s moral restraint despite his grievances.

6 Who is “he”? The Captain or Third Mate?

7 In nineteenth-century maritime culture, directing that a man be served from a plate associated with an animal was a deliberate act of humiliation rather than a matter of hygiene. Duntlin’s complaint indicates not accidental neglect but an intentional effort to degrade his social standing aboard ship, carried out through the steward, who acted under officers’ authority. His response—that he would rather eat from the plate after the dog than after the man who ordered the insult—reverses the intended degradation by asserting a moral hierarchy: the animal is presented as cleaner, and thus more honorable, than the human agent of the affront.